- Company

- Products

- Catalogs

- News & Trends

- Exhibitions

Circulation heater for liquidsconvectionstainless steel

Add to favorites

Compare this product

Characteristics

- Treated product

- for liquids

- Type..

- convection, circulation

- Other characteristics

- stainless steel, explosion-proof, anti-corrosion, in-line, electric

Description

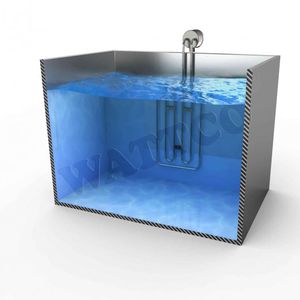

Circulation Heaters, also known as “in line heaters,” have uses in many applications. They can use steel, stainless steel, or titanium depending on the application. Lube oil and waste oil applications often use steel for circulation heaters. This is because it is fairly inexpensive compared to stainless steel counterpart. Water circulation heaters use stainless steel because of its anti-corrosive qualities. In both applications, a pump flows the liquid, such as water or glycerol, through a closed pipe circuit. The liquid is reheated as it flows through the circulation heater. A major consideration for this application is viscosity. Electric circulation heaters generate heat, making the medium less viscous. The less viscous the fluid, the easier it is to pump through a circuit of pipes.

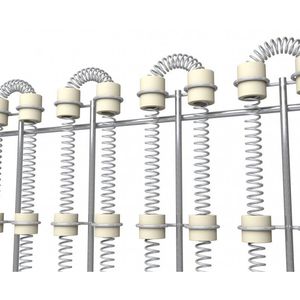

Industrial circulation heaters come in a range of watt densities. Watt densities are specifically designed for the medium they will heat. The required wattage to heat the oil or water is highly correlated to the flow rate (in GPM).

The fluid enters through the inlet closest to the flange heater.

Heat gets applied to the fluid as it flows within a vessel chamber.

The fluid exits the outlet nozzle or flange.

It circulates throughout the piping circuit.

Insulation is often required for vessels to preserve the heat within the vessel. This results in efficient heat application, reducing unnecessary costs through heat loss. Electric circulation heaters can use digital thermocouple probes or RTDs. This allows them to maintain the oil or water at the preferred temperature. Many applications use liquids with low flash point. These require explosion-proof housing (NEMA 7) to avoid potential mishaps.

VIDEO

Catalogs

No catalogs are available for this product.

See all of WATTCO‘s catalogsRelated Searches

- Resistance heater

- WATTCO heater

- Gas heater

- Air heater

- WATTCO electric heater

- WATTCO liquid heater

- Immersion heater

- Cartridge heater

- Tubular resistance heater

- Convection heater

- Circulation heater

- Stainless steel heater

- Band heater

- Duct heater

- Flat resistance heater

- Flexible resistance heater

- Industrial resistance heater

- Stainless steel resistance heater

- Electric band heater

- Preheater

*Prices are pre-tax. They exclude delivery charges and customs duties and do not include additional charges for installation or activation options. Prices are indicative only and may vary by country, with changes to the cost of raw materials and exchange rates.